How Oreo won the Super Bowl

or: the risks and rewards of humor

We’ve talked about how humor is a powerful tool to help your audience listen, understand, and remember your message.

So humor sounds great, right? Well, now you’re probably thinking —

Why doesn’t everybody use humor?

In a word, fear.

Specifically, fear of the dreaded Two C’s: Crickets and Criticism.

Crickets is an old comics’ term for when your joke gets no laughter. None. A silence so complete that you can hear the crickets outside the theater. This is painful. But temporary. You can win the audience back with your very next sentence.

Criticism is when your humor angers or disturbs your audience. Poorly thought out humor can do the exact opposite of communication — it can turn people away from you and your message. And it can produce a chain reaction of disapproval, damaging your reputation far beyond the original audience you offended.

The Two C’s are always there. Because, at its heart —

Humor is risky.

And that’s not, by itself, a bad thing. The risk in humor is actually one of the reasons why we like it. Look at trapeze acts, or Saturday Night Live — watching someone succeed in a risky situation is exhilarating. For the audience, the risk is part of the fun.

For instance, here’s two tweets from business accounts. Both of these were instances from the early 2010’s of large businesses posting a joke about their product and current events. One of these tweets was internationally reviled, finally requiring a public apology from the head of the company. The other was hailed a delightful morsel of marketing genius, and earned positive media coverage far beyond its original Twitter audience. Here they are:

Both took a risk. One was genius, one was a brand-damager. But why? Where did the cringe-y tweet go wrong? And more importantly, where did the fun one go right?

Well, to begin with, we want to —

Understand the audience paradox.

When you (“you” in this article could mean your own self, your client, your product, or your organization) communicate with your audience, who has the power in the relationship, you or them? The answer is yes.

You are the one with the new knowledge. You are the one with the solution to their problem. You are the one with the message. And the audience have given their time to you. You are in a position of power.

Your audience has complete control over where and when to spend their valuable attention. They can leave at any time. And once you’ve lost that attention, your message just echoes into the void. The audience is in a position of power.

As the comedian John Mulaney said:

The audience is both looking up to you and they are Mount Olympus.

Since your audience has the power to decide whether or not you’re being funny, you’re in a vulnerable position when you use humor. Because when somebody says to you “that’s not funny,” guess what? They’re right. If they don’t think it’s funny, it’s not funny to them. It’s not worth trying to explain. It’s not worth arguing the point.

Now, it’s understandable if someone says “that’s not funny” because they don’t get your sense of humor. In fact, the more closely your core audience identifies with your humor, the more likely that those not in the core will be baffled. So there’s no shame in occasionally hearing those crickets.

And a small percentage of the audience will criticize everything and anything you say. “You can’t please everybody” isn’t a consoling platitude, it is the literal truth. And the internet lets you instantly reach a larger number of people who will criticize any message. That’s a given. There will be criticism. There will always be criticism.

The goal, then, is not to give your audience a legitimate reason to criticize your humor. Luckily, this is easy. First, don’t be a jerk. And second—

Always punch up.

The most universal humor is about you and what you love. The next most universal is about people and things that are in a position of power above both you and your audience. That’s “punching up.”

Respect your audience’s power, avoid using humor to make fun of others — and never make fun of people who have less power than you. Mainly because it’s just common decency. And also since it’s vital in building a rapport with your audience.

This is especially important if you have any sort of position of power over the audience. I once scripted an introductory video for the CEO of a Fortune 500 multinational, and I had him mention all the wonderful places he’d been to as part of his job. When he saw the draft, he said he’d actually been on some real grueling trips to unglamorous places in his career, and that’s what he wanted to talk about instead. He wanted the audience to know he’d gone through some of the same grinds they had.

Instead of being the big boss, looking down, he wanted to show that he had the same perspective as the audience. He wanted to stand with them, and punch up.

One way to make sure you’re punching in the right direction is to —

Choose the right style of humor.

There’s a surprising amount of scientific research on what’s funny and why. Psychologists have come up with four styles of humor that all jokes and other forms fall into. It’s a quadrant system based on two axes:

Does the humor build up or tear down?

And does it affect just the person using the humor, or does it affect their relationship with their audience?

Positive effect on relationships = Affiliative humor

Negative effect on relationships = Aggressive humor

Positive effect on self = Self-enhancing humor

Negative effect on self = Self defeating humor

Affiliative humor works best to get your message to your audience. It connects, it shares, it builds empathy. Also, since you’re not out to hurt anybody, Aggressive humor has no place in building or communicating with an audience.

(Look, I know there are comedians who have built successful careers around Aggressive humor. But that’s comedy as entertainment, not humor as communication. If your goal is connection, communication, and understanding, I recommend avoiding Aggressive humor entirely.)

Looking at these humor styles, you can start to see why the cookie-based tweet was such a success. And there’s one more bit of theory I want to tell you about. It gets to the heart of the respective success and failure of the two tweets.

In 2010, Dr. Peter McGraw and doctoral student Caleb Warren presented to the world a scientific theory that many believe explains what audiences will — or won’t — find funny. They call it —

Benign Violation Theory (BVT).

When you think about it, every joke violates some set of rules. It creates a world where something is wrong.

Puns violate the rules of grammar. Cartoons (especially those with coyotes) violate the laws of physics. Horses do not walk into bars (well, maybe sometimes). But what makes these violations funny, and not offensive?

They are all benign — there’s no harm done. Language remains unharmed by the pun. The coyote waddles away after being flattened into a varmint pancake by the anvil. The bartender simply asks the horse, “Hey, fella, why the long face?”

And that’s why punching up is funny. Everyone understands that the joke is, at worst, an irritation to the target. It’s not a crushing blow — the target will be fine. We can just enjoy the humor. And if the target is in a position of power over both you and your audience, then your humor becomes Affiliative.

So with the Humor Styles and the Benign Violation Theory in mind, let’s take another look at those two tweets. Both were tweets referencing current events. You probably remember the Oreo tweet, and what a sensation it was. One of the things that made its use of humor so successful was —

Oreo benignly punched up.

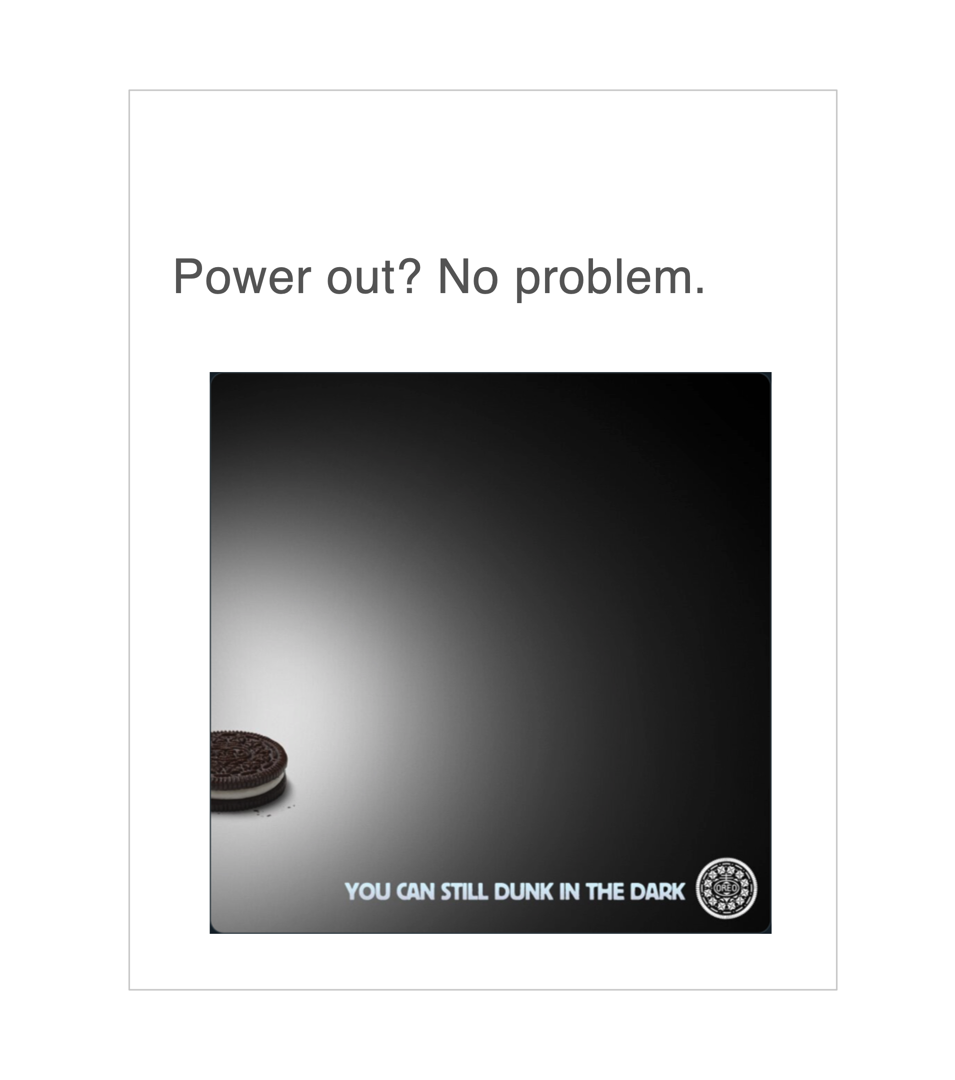

At the Super Bowl XLVII in 2013, there was a partial power outage that darkened the New Orleans Superdome and stopped play for about 34 minutes. While the blackout was still going on, the social team working for Oreo posted this now-famous tweet:

Even though the Oreo social team were representing a major product from a large multinational snacks producer, they were poking fun at a hugely popular and lavish spectacle put on by a professional sports league whose teams were worth an estimated 78.4 billion dollars in 2016. Pretty much the entire day of the Super Bowl belongs to the NFL. So Oreo was definitely punching up.

And the Oreo social team wisely waited to make sure the blackout was not a result of terrorism, or that anyone was hurt. Yes, this was a major inconvenience for a major event. But after 34 minutes, the power was restored, and the game resumed. It was a huge embarrassment for the people responsible for the stadium’s power grid, but other than that, no harm done. The event was benign.

Everything about the tweet benignly punches up:

The tweet starts with a question about how things are going for the reader, not the Superbowl or the NFL. It talks directly to the audience. The connection to the blackout is all context, especially since the Oreo team managed to post the tweet while the power was still out. You can read an excellent oral history of the team and process here.

“You can still dunk in the dark” is worded as a helpful suggestion: you can dunk in the dark. If you want.

The Oreo cookie seems to be in a blackout, same as everyone at the New Orleans Superdome. It is sharing the inconvenience with them. And it’s partly out of the frame, almost as if it’s shy to intrude.

I’m tickled by the use of the verb “dunk,” long part of Oreo lore, but also a term from an entirely different sport than football. It’s a playful “twang” in the music of the tweet.

The Oreo tweet was a bit of innocent cheekiness that is still fun to see years later. Not so with an infamous tweet from the Kenneth Cole account from 2011. Because in that tweet (long since deleted and apologized for ) —

Kenneth Cole punched down on a bad situation.

In the beginning of 2011, a series of protests started in Egypt that ultimately led to the overthrow of a 30-year regime. The change did not come easy. Protesters were hurt, protesters were killed. And here’s what the Kenneth Cole twitter account posted during the peak of the unrest:

ABC News described this “tacky” tweet as “exploiting a democratic movement in which people have died in order to sell shoes and handbags.” And the tweet added insult to insult by using the #Cairo hashtag.

The situation was not benign. The people suffering were definitely not as advantaged as an American fashion house. This was not a time or place for humor. The tweet was terrible from start to finish.

Contrast how you’re feeling now, to how you felt while reading about the Oreo tweet. That Oreo tweet was fun, right? A little energizing? You might have even started to think about how to connect with your audience using humor. Because, as some malfunctioning electrical equipment and an observant cookie proved—

Humor is a risk that creates empathy.

If you do it right.

It’s why I always emphasize that humor should be based on you and what you love. If that's the focus of your humor, you’re never punching down. If you’re talking about what you love, your humor is always benign. And it’s how you can create affiliative humor, to form a connection between you and your audience.

So anyway, a grasshopper walks into a bar…